10 💻 PCA

⚠️ Note on Slides: If you encounter broken links in the PDF slides (

module_2_PCA_&_CA.pdf), please refer to the “Online Resources and References” section at the end of this chapter for updated and working links.

10.1 Introduction to Principal Component Analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a powerful dimensionality reduction technique used to transform a large set of variables into a smaller set of uncorrelated variables called principal components. These components capture the maximum variance in the data while reducing complexity.

10.1.1 Key Concepts

- Dimensionality Reduction: Reduce the number of variables while retaining most of the information

- Variance Preservation: Principal components are ordered by the amount of variance they explain

- Uncorrelated Components: Each principal component is orthogonal (uncorrelated) to the others

- Data Standardization: Often necessary when variables are on different scales

10.2 Required Packages

We will use the following packages throughout this chapter:

library(FactoMineR) # For PCA analysis

library(factoextra) # For visualization

library(ISLR2) # For datasets10.3 17.1 PCA with FactoMineR Package

10.3.1 17.1.1 Example 1: Simple 2D Dataset

Let’s start with a simple example to understand the fundamentals of PCA.

10.3.1.1 Step 1: Create and Explore the Data

X <- data.frame(

Var1 = c(2, 1, -1, -2),

Var2 = c(2, -1, 1, -2)

)

rownames(X) <- c("i1", "i2", "i3", "i4")

X

#> Var1 Var2

#> i1 2 2

#> i2 1 -1

#> i3 -1 1

#> i4 -2 -210.3.1.2 Step 2: Calculate Covariance Matrix and Inertia

# Calculate means

mean(X[,1]) # mean of Var1

#> [1] 0

mean(X[,2]) # mean of Var2

#> [1] 0

# Variance-covariance matrix

# The constant (n-1)/n adjusts for the variance-covariance matrix used in lectures

S <- var(X) * (3/4)

S

#> Var1 Var2

#> Var1 2.5 1.5

#> Var2 1.5 2.5

# Inertia (sum of diagonal elements = sum of variances)

Inertia <- sum(diag(S))

Inertia

#> [1] 510.3.1.3 Step 3: Eigen-analysis on Covariance Matrix

eigen(S) # gives the eigen-values and eigen-vectors

#> eigen() decomposition

#> $values

#> [1] 4 1

#>

#> $vectors

#> [,1] [,2]

#> [1,] 0.7071068 -0.7071068

#> [2,] 0.7071068 0.707106810.3.1.4 Step 4: Eigen-analysis on Correlation Matrix

# Correlation matrix

R <- cor(X)

eigenan <- eigen(R) # eigen analysis of R

eigenan

#> eigen() decomposition

#> $values

#> [1] 1.6 0.4

#>

#> $vectors

#> [,1] [,2]

#> [1,] 0.7071068 -0.7071068

#> [2,] 0.7071068 0.7071068

# Sum of eigenvalues equals p (number of variables)

sum(eigenan$values)

#> [1] 2

# Normalized data (centered and scaled)

Z <- scale(X)

var(Z) # is the correlation matrix

#> Var1 Var2

#> Var1 1.0 0.6

#> Var2 0.6 1.010.3.1.5 Step 5: Perform PCA on Covariance Matrix

PCA with the covariance matrix uses only centered data. For PCA on the correlation matrix (normed PCA), use scale.unit = TRUE (default option).

Note on Correlation: The correlation between two variables \(X_1\) and \(X_2\) is: \[\rho = \frac{cov(X_1, X_2)}{\sigma_{X_1} \sigma_{X_2}}\]

where \(cov(X_1, X_2)\) is the covariance, and \(\sigma_{X_1} = \sqrt{Var(X_1)}\) is the standard deviation of \(X_1\).

res.pca.cov <- PCA(X, scale.unit = FALSE, graph = FALSE)

print(res.pca.cov)

#> **Results for the Principal Component Analysis (PCA)**

#> The analysis was performed on 4 individuals, described by 2 variables

#> *The results are available in the following objects:

#>

#> name description

#> 1 "$eig" "eigenvalues"

#> 2 "$var" "results for the variables"

#> 3 "$var$coord" "coord. for the variables"

#> 4 "$var$cor" "correlations variables - dimensions"

#> 5 "$var$cos2" "cos2 for the variables"

#> 6 "$var$contrib" "contributions of the variables"

#> 7 "$ind" "results for the individuals"

#> 8 "$ind$coord" "coord. for the individuals"

#> 9 "$ind$cos2" "cos2 for the individuals"

#> 10 "$ind$contrib" "contributions of the individuals"

#> 11 "$call" "summary statistics"

#> 12 "$call$centre" "mean of the variables"

#> 13 "$call$ecart.type" "standard error of the variables"

#> 14 "$call$row.w" "weights for the individuals"

#> 15 "$call$col.w" "weights for the variables"10.3.1.6 Step 6: Examine Eigenvalues

We have \(p = 2 = min(n-1, p) = min(3, 2)\) eigenvalues: 4 and 1. The inertia \(Inertia = 4 + 1 = 5\) is the sum of the variances of the variables.

res.pca.cov$eig

#> eigenvalue percentage of variance

#> comp 1 4 80

#> comp 2 1 20

#> cumulative percentage of variance

#> comp 1 80

#> comp 2 10010.3.1.7 Step 7: Examine Variables and Individuals

res.pca.cov$var

#> $coord

#> Dim.1 Dim.2

#> Var1 1.414214 -0.7071068

#> Var2 1.414214 0.7071068

#>

#> $cor

#> Dim.1 Dim.2

#> Var1 0.8944272 -0.4472136

#> Var2 0.8944272 0.4472136

#>

#> $cos2

#> Dim.1 Dim.2

#> Var1 0.8 0.2

#> Var2 0.8 0.2

#>

#> $contrib

#> Dim.1 Dim.2

#> Var1 50 50

#> Var2 50 50

res.pca.cov$ind

#> $coord

#> Dim.1 Dim.2

#> i1 2.82842712474619073503845 -0.000000000000000006357668

#> i2 0.00000000000000001271534 -1.414213562373095367519227

#> i3 -0.00000000000000040992080 1.414213562373094923430017

#> i4 -2.82842712474619029094924 0.000000000000000204960400

#>

#> $cos2

#> Dim.1

#> i1 1.00000000000000044408920985006261616945267

#> i2 0.00000000000000000000000000000000008083988

#> i3 0.00000000000000000000000000000008401753104

#> i4 1.00000000000000022204460492503130808472633

#> Dim.2

#> i1 0.000000000000000000000000000000000005052492

#> i2 1.000000000000000444089209850062616169452667

#> i3 0.999999999999999777955395074968691915273666

#> i4 0.000000000000000000000000000000005251095690

#>

#> $contrib

#> Dim.1

#> i1 50.000000000000021316282072803005576133728

#> i2 0.000000000000000000000000000000001010498

#> i3 0.000000000000000000000000000001050219138

#> i4 50.000000000000014210854715202003717422485

#> Dim.2

#> i1 0.000000000000000000000000000000001010498

#> i2 50.000000000000021316282072803005576133728

#> i3 49.999999999999985789145284797996282577515

#> i4 0.000000000000000000000000000001050219138

#>

#> $dist

#> i1 i2 i3 i4

#> 2.828427 1.414214 1.414214 2.82842710.3.2 17.1.2 Example 2: Student Grades Dataset

Now let’s work with a more realistic example: student grades in three subjects.

10.3.2.1 Step 1: Prepare the Data

A <- matrix(c(9,12,10,15,9,10,5,10,8,11,13,14,11,13,8,3,15,10),

nrow=6, byrow=TRUE)

A

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> [1,] 9 12 10

#> [2,] 15 9 10

#> [3,] 5 10 8

#> [4,] 11 13 14

#> [5,] 11 13 8

#> [6,] 3 15 10

Nframe <- as.data.frame(A)

# Set row and column names

m1 <- c("Alex", "Bea", "Claudio", "Damien", "Emilie", "Fran")

m2 <- c("Biostatistics", "Economics", "English")

rownames(A) <- m1

colnames(A) <- m2

head(A)

#> Biostatistics Economics English

#> Alex 9 12 10

#> Bea 15 9 10

#> Claudio 5 10 8

#> Damien 11 13 14

#> Emilie 11 13 8

#> Fran 3 15 1010.3.2.2 Step 2: Perform PCA on Correlation Matrix

res.pca.cor <- PCA(A, scale.unit = TRUE, graph = FALSE)

print(res.pca.cor)

#> **Results for the Principal Component Analysis (PCA)**

#> The analysis was performed on 6 individuals, described by 3 variables

#> *The results are available in the following objects:

#>

#> name description

#> 1 "$eig" "eigenvalues"

#> 2 "$var" "results for the variables"

#> 3 "$var$coord" "coord. for the variables"

#> 4 "$var$cor" "correlations variables - dimensions"

#> 5 "$var$cos2" "cos2 for the variables"

#> 6 "$var$contrib" "contributions of the variables"

#> 7 "$ind" "results for the individuals"

#> 8 "$ind$coord" "coord. for the individuals"

#> 9 "$ind$cos2" "cos2 for the individuals"

#> 10 "$ind$contrib" "contributions of the individuals"

#> 11 "$call" "summary statistics"

#> 12 "$call$centre" "mean of the variables"

#> 13 "$call$ecart.type" "standard error of the variables"

#> 14 "$call$row.w" "weights for the individuals"

#> 15 "$call$col.w" "weights for the variables"10.3.2.3 Step 3: Examine Eigenvalues

res.pca.cor$eig

#> eigenvalue percentage of variance

#> comp 1 1.5000000 50.00000

#> comp 2 1.1830127 39.43376

#> comp 3 0.3169873 10.56624

#> cumulative percentage of variance

#> comp 1 50.00000

#> comp 2 89.43376

#> comp 3 100.00000

get_eigenvalue(res.pca.cor)

#> eigenvalue variance.percent

#> Dim.1 1.5000000 50.00000

#> Dim.2 1.1830127 39.43376

#> Dim.3 0.3169873 10.56624

#> cumulative.variance.percent

#> Dim.1 50.00000

#> Dim.2 89.43376

#> Dim.3 100.00000Interpretation: Kaiser’s rule suggests \(q = 2\) components because the eigenvalue mean is 1 (with 89% of explained variance). The rule of thumb gives \(q = 2\) because the first 2 dimensions explain 89% of the variance/inertia.

10.3.2.4 Step 4: Examine Variables

res.pca.cor$var

#> $coord

#> Dim.1 Dim.2 Dim.3

#> Biostatistics -0.866025403784438041477 0.3535534 0.3535534

#> Economics 0.866025403784439040678 0.3535534 0.3535534

#> English 0.000000000000001047394 0.9659258 -0.2588190

#>

#> $cor

#> Dim.1 Dim.2 Dim.3

#> Biostatistics -0.866025403784438041477 0.3535534 0.3535534

#> Economics 0.866025403784439151700 0.3535534 0.3535534

#> English 0.000000000000001047394 0.9659258 -0.2588190

#>

#> $cos2

#> Dim.1

#> Biostatistics 0.749999999999999000799277837359113619

#> Economics 0.750000000000000888178419700125232339

#> English 0.000000000000000000000000000001097035

#> Dim.2 Dim.3

#> Biostatistics 0.1250000 0.1250000

#> Economics 0.1250000 0.1250000

#> English 0.9330127 0.0669873

#>

#> $contrib

#> Dim.1

#> Biostatistics 49.99999999999993605115378159098327160

#> Economics 50.00000000000005684341886080801486969

#> English 0.00000000000000000000000000007313567

#> Dim.2 Dim.3

#> Biostatistics 10.56624 39.43376

#> Economics 10.56624 39.43376

#> English 78.86751 21.1324910.3.2.5 Step 5: Correlations Between Variables and Components

res.pca.cor$var$cor

#> Dim.1 Dim.2 Dim.3

#> Biostatistics -0.866025403784438041477 0.3535534 0.3535534

#> Economics 0.866025403784439151700 0.3535534 0.3535534

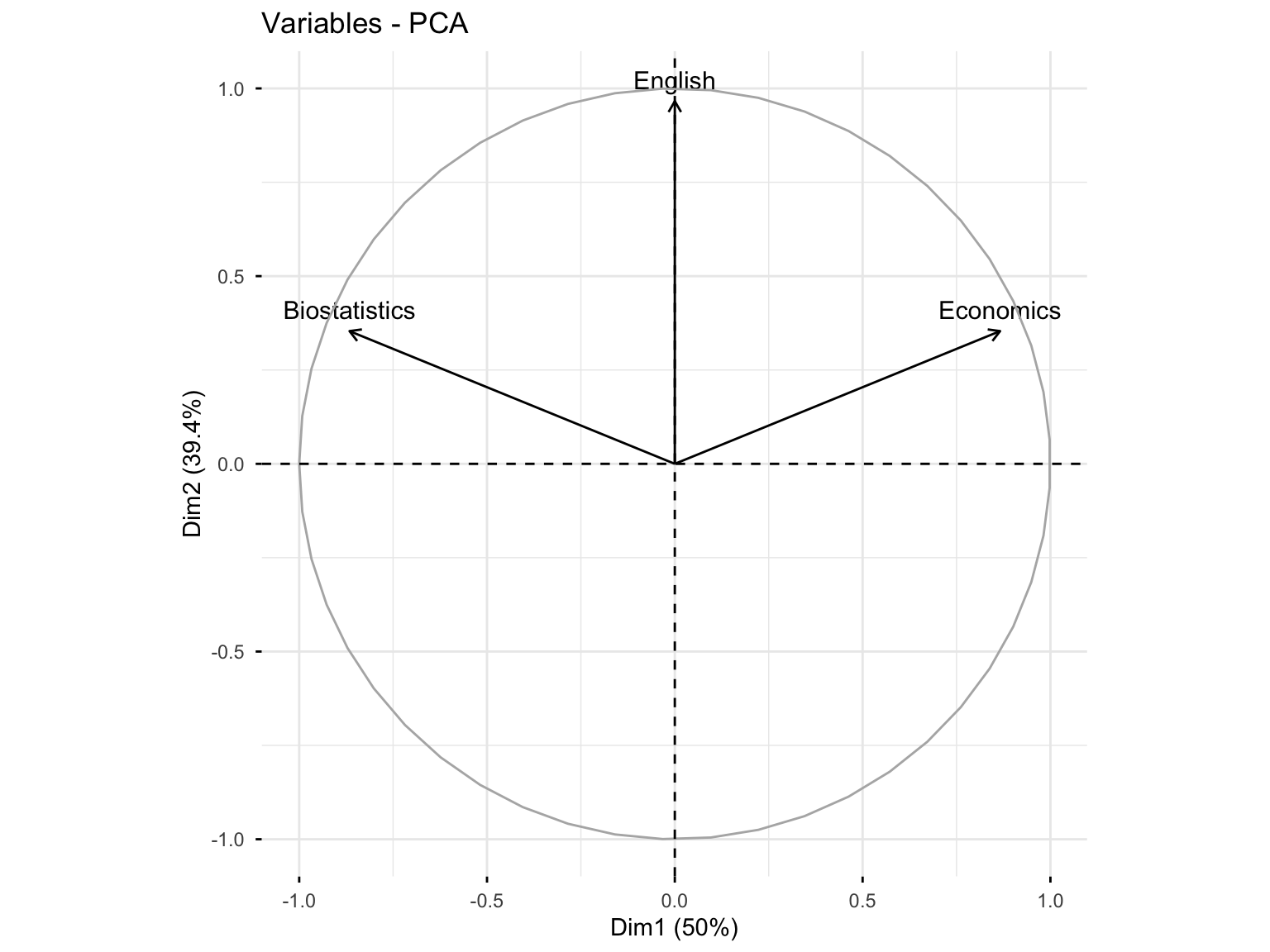

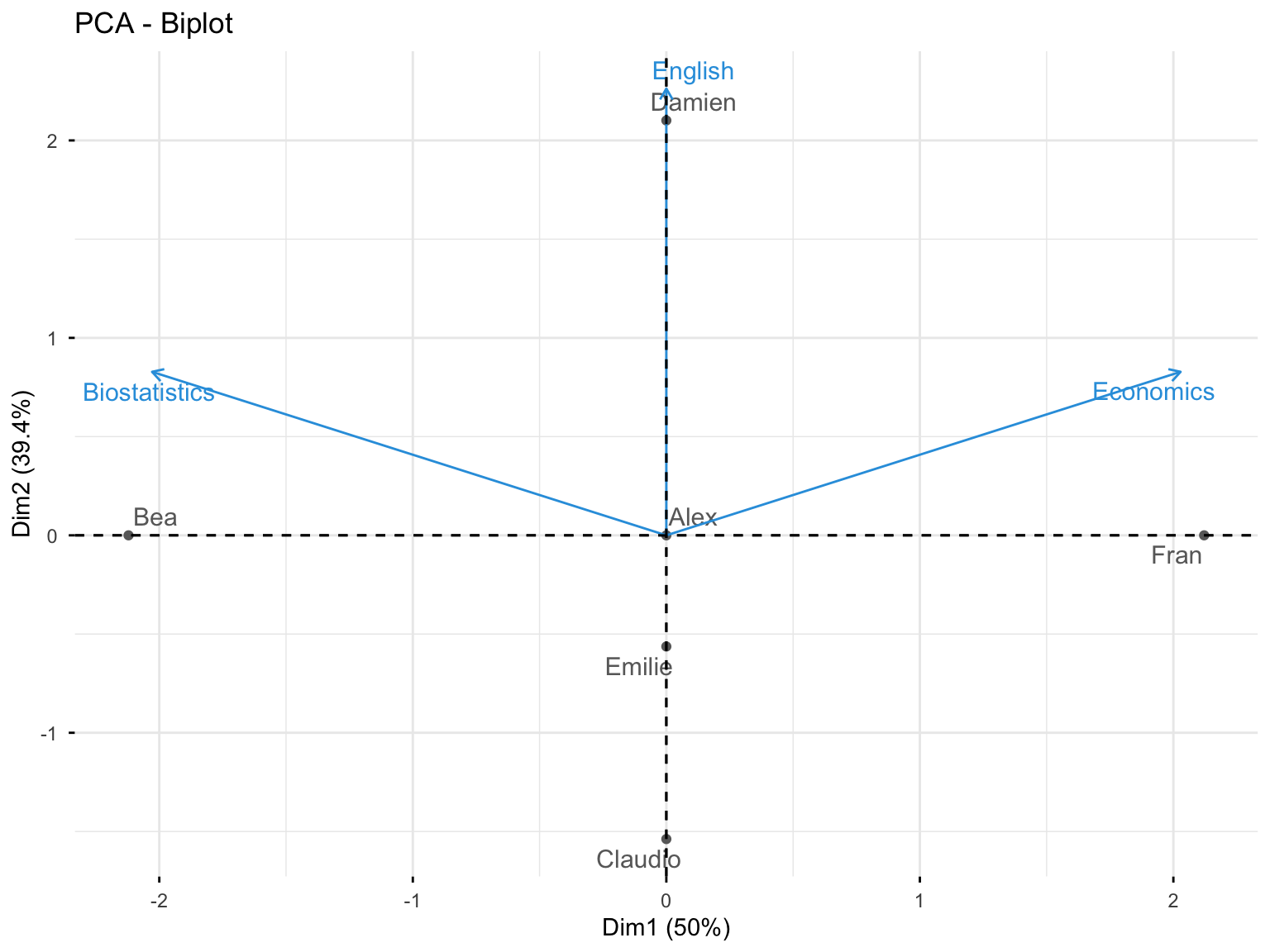

#> English 0.000000000000001047394 0.9659258 -0.2588190Interpretation: The first axis is correlated with Biostatistics (+0.86) and Economics (-0.86). The second axis is correlated to English (0.96). The two components are correlated with at least one variable, so \(q = 2\) may be considered to reduce the dimension from \(p = 3\).

10.3.2.6 Step 6: Coordinates of Variables

res.pca.cor$var$coord

#> Dim.1 Dim.2 Dim.3

#> Biostatistics -0.866025403784438041477 0.3535534 0.3535534

#> Economics 0.866025403784439040678 0.3535534 0.3535534

#> English 0.000000000000001047394 0.9659258 -0.258819010.3.2.7 Step 7: Quality of Representation (cos²)

res.pca.cor$var$cos2

#> Dim.1

#> Biostatistics 0.749999999999999000799277837359113619

#> Economics 0.750000000000000888178419700125232339

#> English 0.000000000000000000000000000001097035

#> Dim.2 Dim.3

#> Biostatistics 0.1250000 0.1250000

#> Economics 0.1250000 0.1250000

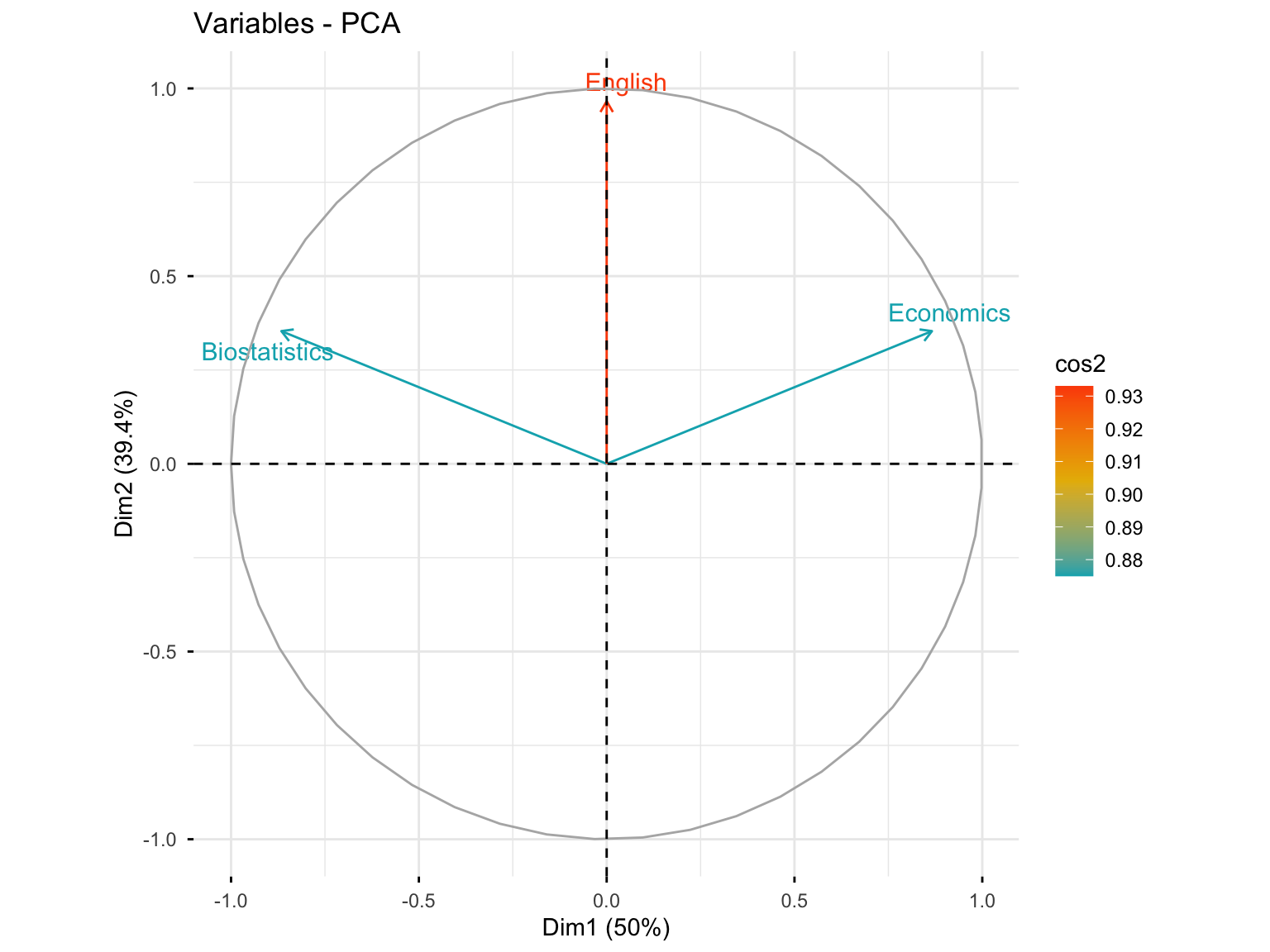

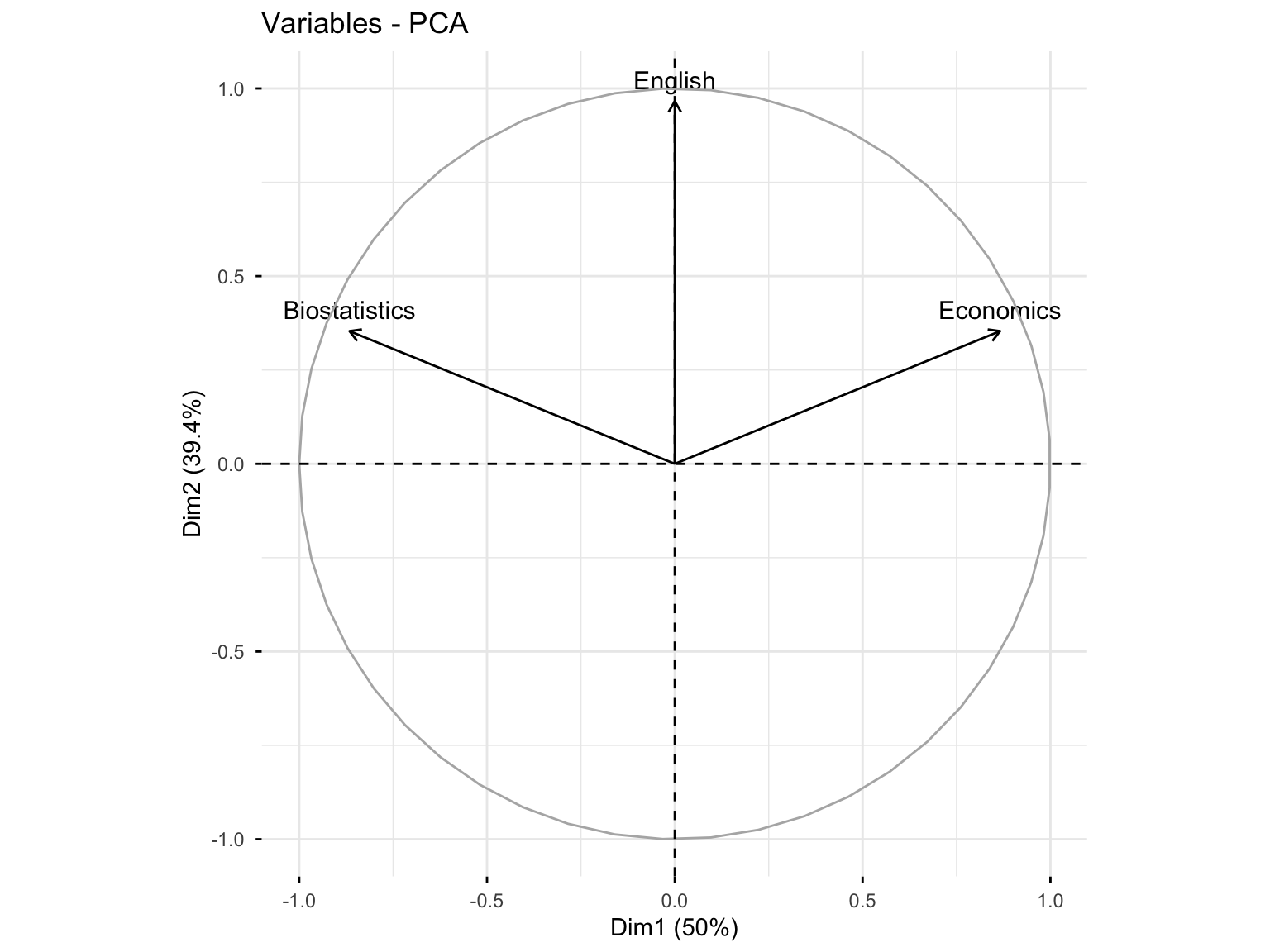

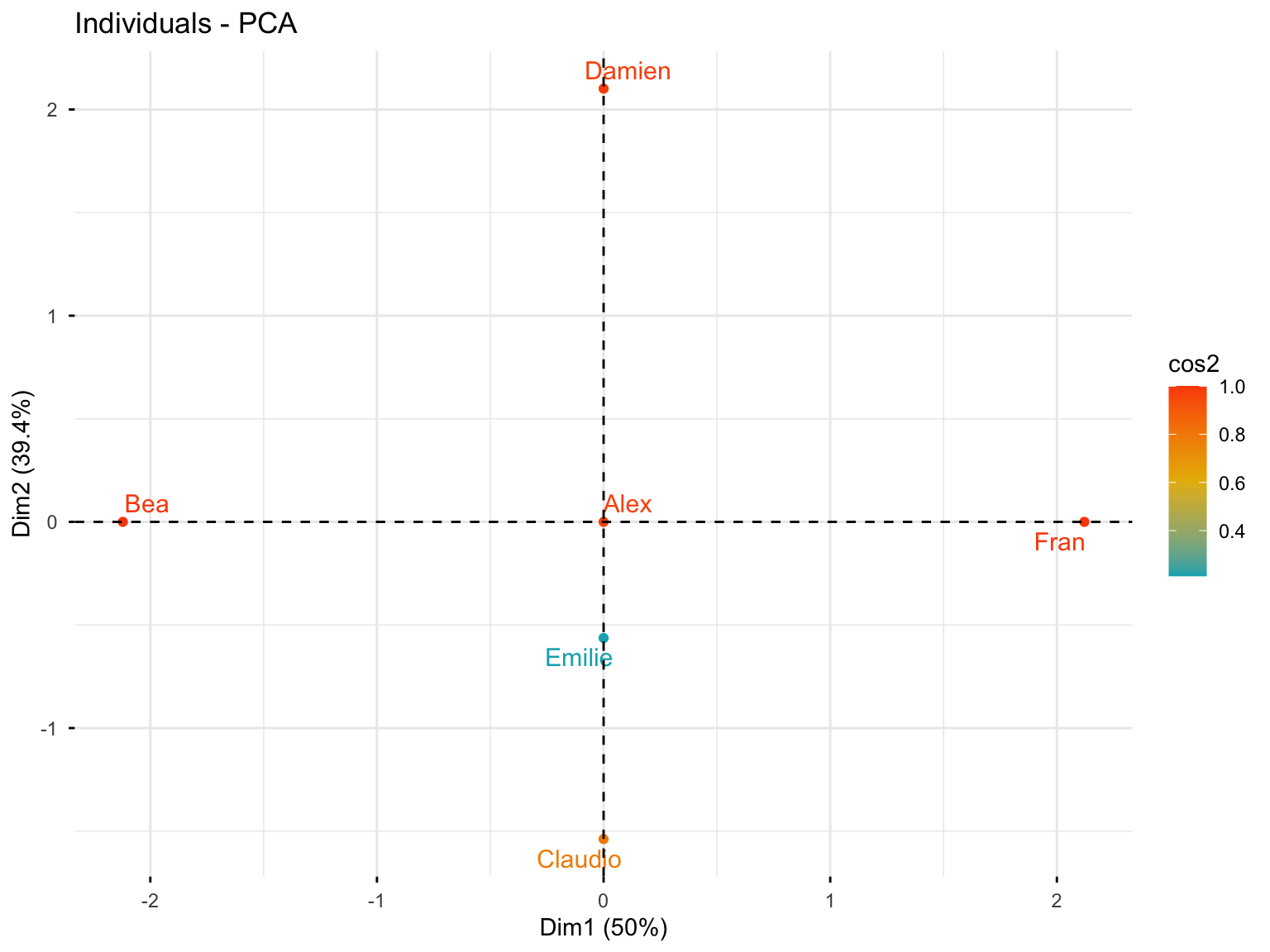

#> English 0.9330127 0.0669873Interpretation: Biostatistics and Economics are well represented in the first dimension (75%), while English is very well represented in the second axis (93%). In the first plane (Dim.1 and Dim.2), Biostatistics and Economics are well represented (75% + 12.5% = 87.5%), and English is very well represented (93% + 0% = 93%).

10.3.2.8 Step 8: Contributions of Variables

res.pca.cor$var$contrib

#> Dim.1

#> Biostatistics 49.99999999999993605115378159098327160

#> Economics 50.00000000000005684341886080801486969

#> English 0.00000000000000000000000000007313567

#> Dim.2 Dim.3

#> Biostatistics 10.56624 39.43376

#> Economics 10.56624 39.43376

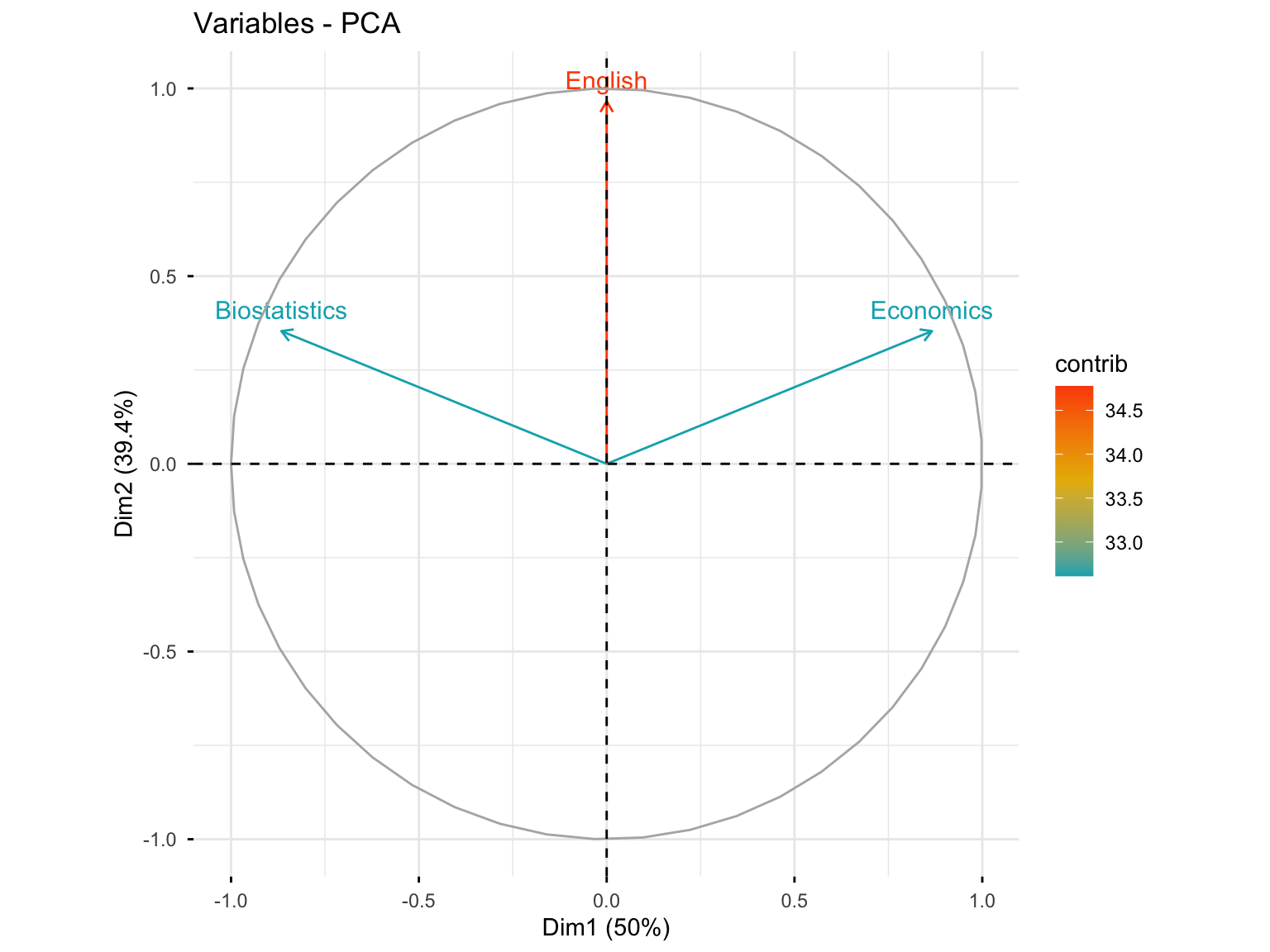

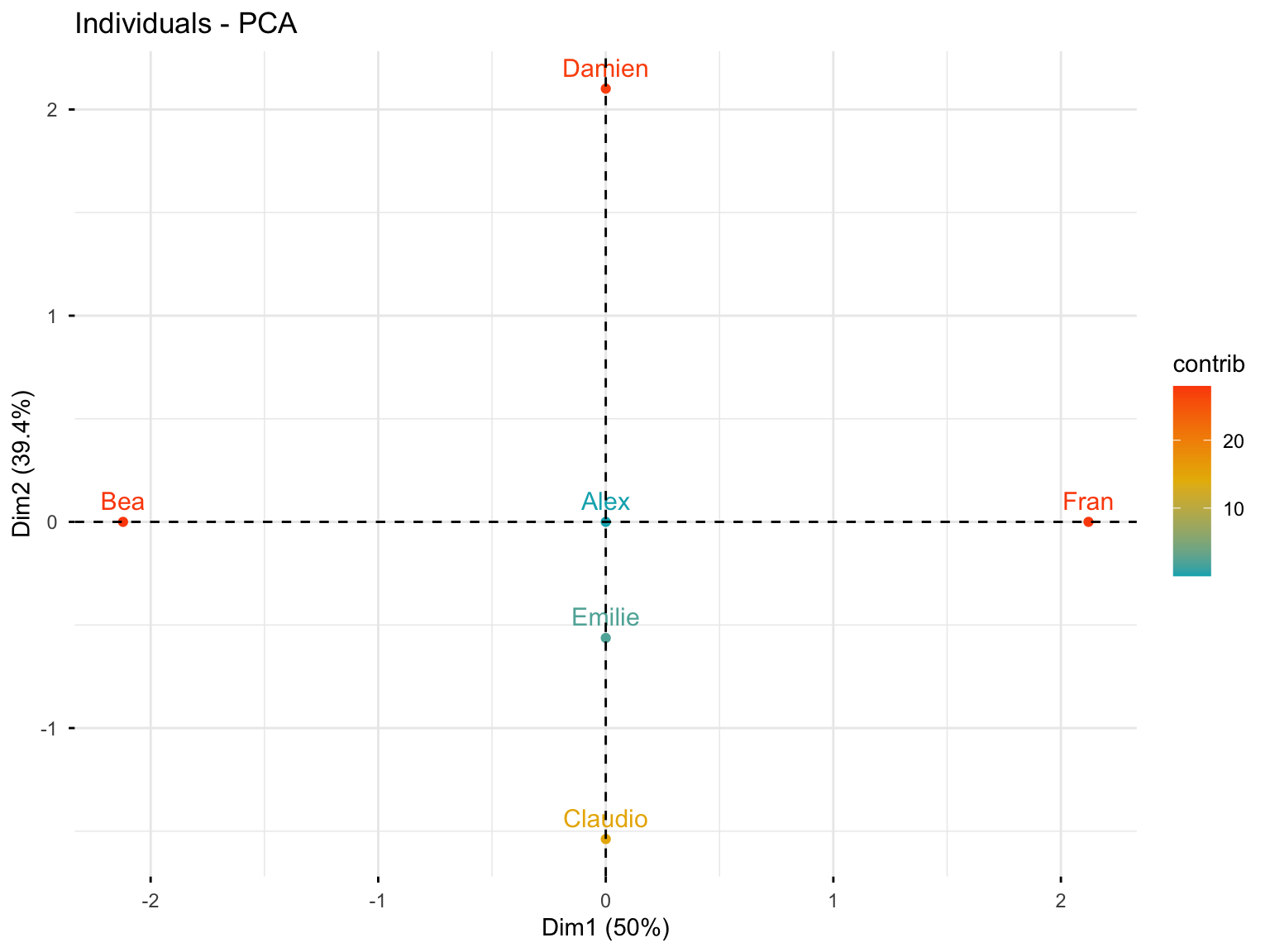

#> English 78.86751 21.13249Interpretation: Biostatistics and Economics contribute to the construction of the first dimension (50%), while English contributes highly to the construction of the second axis (78.8%). In the first plane, the contribution of Biostatistics and Economics is 50% + 10.5% = 60.5%, and that of English is 78.8%.

10.3.2.9 Step 9: Description of Dimensions

dimdesc(res.pca.cor, axes = 1)

#> $Dim.1

#>

#> Link between the variable and the continuous variables (R-square)

#> =================================================================================

#> correlation p.value

#> Economics 0.8660254 0.02572142

#> Biostatistics -0.8660254 0.0257214210.3.2.10 Step 10: Contributions of First Two Dimensions

res.pca.cor$var$contrib[, 1:2]

#> Dim.1

#> Biostatistics 49.99999999999993605115378159098327160

#> Economics 50.00000000000005684341886080801486969

#> English 0.00000000000000000000000000007313567

#> Dim.2

#> Biostatistics 10.56624

#> Economics 10.56624

#> English 78.8675110.3.3 17.1.3 Visualizations

10.3.3.2 Variables Plot with Quality of Representation

fviz_pca_var(res.pca.cor, col.var = "cos2",

gradient.cols = c("#00AFBB", "#E7B800", "#FC4E07"),

repel = TRUE)

10.3.3.3 Variables with High Quality of Representation (cos² > 0.6)

fviz_pca_var(res.pca.cor, select.var = list(cos2 = 0.6))

10.3.3.4 Variables Plot with Contributions

fviz_pca_var(res.pca.cor, col.var = "contrib",

gradient.cols = c("#00AFBB", "#E7B800", "#FC4E07"))

10.3.3.5 Biplot: Variables and Individuals

fviz_pca_biplot(res.pca.cor, repel = TRUE,

col.var = "#2E9FDF", # Variables color

col.ind = "#696969" # Individuals color

)

10.3.4 17.1.4 Analysis of Individuals

10.3.4.1 Individuals Information

res.pca.cor$ind

#> $coord

#> Dim.1 Dim.2

#> Alex 0.0000000000000002653034 -0.000000000000000941663

#> Bea -2.1213203435596423851450 0.000000000000001237395

#> Claudio -0.0000000000000022171779 -1.538189001320852344890

#> Damien 0.0000000000000026937746 2.101205251626097503248

#> Emilie 0.0000000000000001895371 -0.563016250305248155961

#> Fran 2.1213203435596428292342 -0.000000000000002975084

#> Dim.3

#> Alex -0.00000000000000007994654

#> Bea 0.00000000000000015526499

#> Claudio -0.79622521701812609684623

#> Damien -0.29143865656241157990891

#> Emilie 1.08766387358053817635550

#> Fran 0.00000000000000002468473

#>

#> $cos2

#> Dim.1

#> Alex 0.07137976857538211317155685264879139140

#> Bea 1.00000000000000022204460492503130808473

#> Claudio 0.00000000000000000000000000000163862588

#> Damien 0.00000000000000000000000000000161253810

#> Emilie 0.00000000000000000000000000000002394954

#> Fran 0.99999999999999977795539507496869191527

#> Dim.2

#> Alex 0.8992501752497785716400358069222420454

#> Bea 0.0000000000000000000000000000003402549

#> Claudio 0.7886751345948129765517364830884616822

#> Damien 0.9811252243246878501636842884181533009

#> Emilie 0.2113248654051877173376539076343760826

#> Fran 0.0000000000000000000000000000019669168

#> Dim.3

#> Alex 0.006481699860810073883510273873298501712

#> Bea 0.000000000000000000000000000000005357159

#> Claudio 0.211324865405187134470565979427192360163

#> Damien 0.018874775675311854933324795524640649091

#> Emilie 0.788675134594813309618643870635423809290

#> Fran 0.000000000000000000000000000000000135408

#>

#> $contrib

#> Dim.1

#> Alex 0.0000000000000000000000000000007820654

#> Bea 50.0000000000000000000000000000000000000

#> Claudio 0.0000000000000000000000000000546208628

#> Damien 0.0000000000000000000000000000806269052

#> Emilie 0.0000000000000000000000000000003991590

#> Fran 50.0000000000000213162820728030055761337

#> Dim.2

#> Alex 0.00000000000000000000000000001249253

#> Bea 0.00000000000000000000000000002157130

#> Claudio 33.33333333333337833437326480634510517

#> Damien 62.20084679281458051036679535172879696

#> Emilie 4.46581987385206335972043234505690634

#> Fran 0.00000000000000000000000000012469753

#> Dim.3

#> Alex 0.00000000000000000000000000000033605182

#> Bea 0.00000000000000000000000000000126751744

#> Claudio 33.33333333333333570180911920033395290375

#> Damien 4.46581987385203582618942164117470383644

#> Emilie 62.20084679281465867006772896274924278259

#> Fran 0.00000000000000000000000000000003203788

#>

#> $dist

#> Alex Bea

#> 0.0000000000000009930137 2.1213203435596419410558

#> Claudio Damien

#> 1.7320508075688780813550 2.1213203435596419410558

#> Emilie Fran

#> 1.2247448713915896068016 2.121320343559642829234210.3.4.2 Individuals: Coordinates

res.pca.cor$ind$coord

#> Dim.1 Dim.2

#> Alex 0.0000000000000002653034 -0.000000000000000941663

#> Bea -2.1213203435596423851450 0.000000000000001237395

#> Claudio -0.0000000000000022171779 -1.538189001320852344890

#> Damien 0.0000000000000026937746 2.101205251626097503248

#> Emilie 0.0000000000000001895371 -0.563016250305248155961

#> Fran 2.1213203435596428292342 -0.000000000000002975084

#> Dim.3

#> Alex -0.00000000000000007994654

#> Bea 0.00000000000000015526499

#> Claudio -0.79622521701812609684623

#> Damien -0.29143865656241157990891

#> Emilie 1.08766387358053817635550

#> Fran 0.0000000000000000246847310.3.4.3 Individuals: Quality of Representation

res.pca.cor$ind$cos2

#> Dim.1

#> Alex 0.07137976857538211317155685264879139140

#> Bea 1.00000000000000022204460492503130808473

#> Claudio 0.00000000000000000000000000000163862588

#> Damien 0.00000000000000000000000000000161253810

#> Emilie 0.00000000000000000000000000000002394954

#> Fran 0.99999999999999977795539507496869191527

#> Dim.2

#> Alex 0.8992501752497785716400358069222420454

#> Bea 0.0000000000000000000000000000003402549

#> Claudio 0.7886751345948129765517364830884616822

#> Damien 0.9811252243246878501636842884181533009

#> Emilie 0.2113248654051877173376539076343760826

#> Fran 0.0000000000000000000000000000019669168

#> Dim.3

#> Alex 0.006481699860810073883510273873298501712

#> Bea 0.000000000000000000000000000000005357159

#> Claudio 0.211324865405187134470565979427192360163

#> Damien 0.018874775675311854933324795524640649091

#> Emilie 0.788675134594813309618643870635423809290

#> Fran 0.00000000000000000000000000000000013540810.3.4.4 Individuals: Contributions

res.pca.cor$ind$contrib

#> Dim.1

#> Alex 0.0000000000000000000000000000007820654

#> Bea 50.0000000000000000000000000000000000000

#> Claudio 0.0000000000000000000000000000546208628

#> Damien 0.0000000000000000000000000000806269052

#> Emilie 0.0000000000000000000000000000003991590

#> Fran 50.0000000000000213162820728030055761337

#> Dim.2

#> Alex 0.00000000000000000000000000001249253

#> Bea 0.00000000000000000000000000002157130

#> Claudio 33.33333333333337833437326480634510517

#> Damien 62.20084679281458051036679535172879696

#> Emilie 4.46581987385206335972043234505690634

#> Fran 0.00000000000000000000000000012469753

#> Dim.3

#> Alex 0.00000000000000000000000000000033605182

#> Bea 0.00000000000000000000000000000126751744

#> Claudio 33.33333333333333570180911920033395290375

#> Damien 4.46581987385203582618942164117470383644

#> Emilie 62.20084679281465867006772896274924278259

#> Fran 0.0000000000000000000000000000000320378810.3.4.5 Individuals Plot with Contributions

fviz_pca_ind(res.pca.cor, col.ind = "contrib",

gradient.cols = c("#00AFBB", "#E7B800", "#FC4E07"))

10.3.4.6 Individuals Plot with Quality of Representation

fviz_pca_ind(res.pca.cor, col.ind = "cos2",

gradient.cols = c("#00AFBB", "#E7B800", "#FC4E07"),

repel = TRUE)

10.3.5 17.1.5 Exporting Results

10.3.5.1 Save Figures as PDF

pdf("PCA.pdf")

fviz_pca_var(res.pca.cor)

fviz_pca_ind(res.pca.cor)

dev.off()10.3.5.2 Save Figures as PNG

png("PCA%03d.png", width = 800, height = 600)

fviz_pca_var(res.pca.cor)

fviz_pca_ind(res.pca.cor)

dev.off()10.3.5.3 Export Results to Text Files

write.table(res.pca.cor$eig, "eigenvalues.txt", sep = "\t")

write.table(res.pca.cor$var$coord, "variables_coordinates.txt", sep = "\t")

write.table(res.pca.cor$ind$coord, "individuals_coordinates.txt", sep = "\t")10.4 17.2 PCA with Base R: prcomp() Function

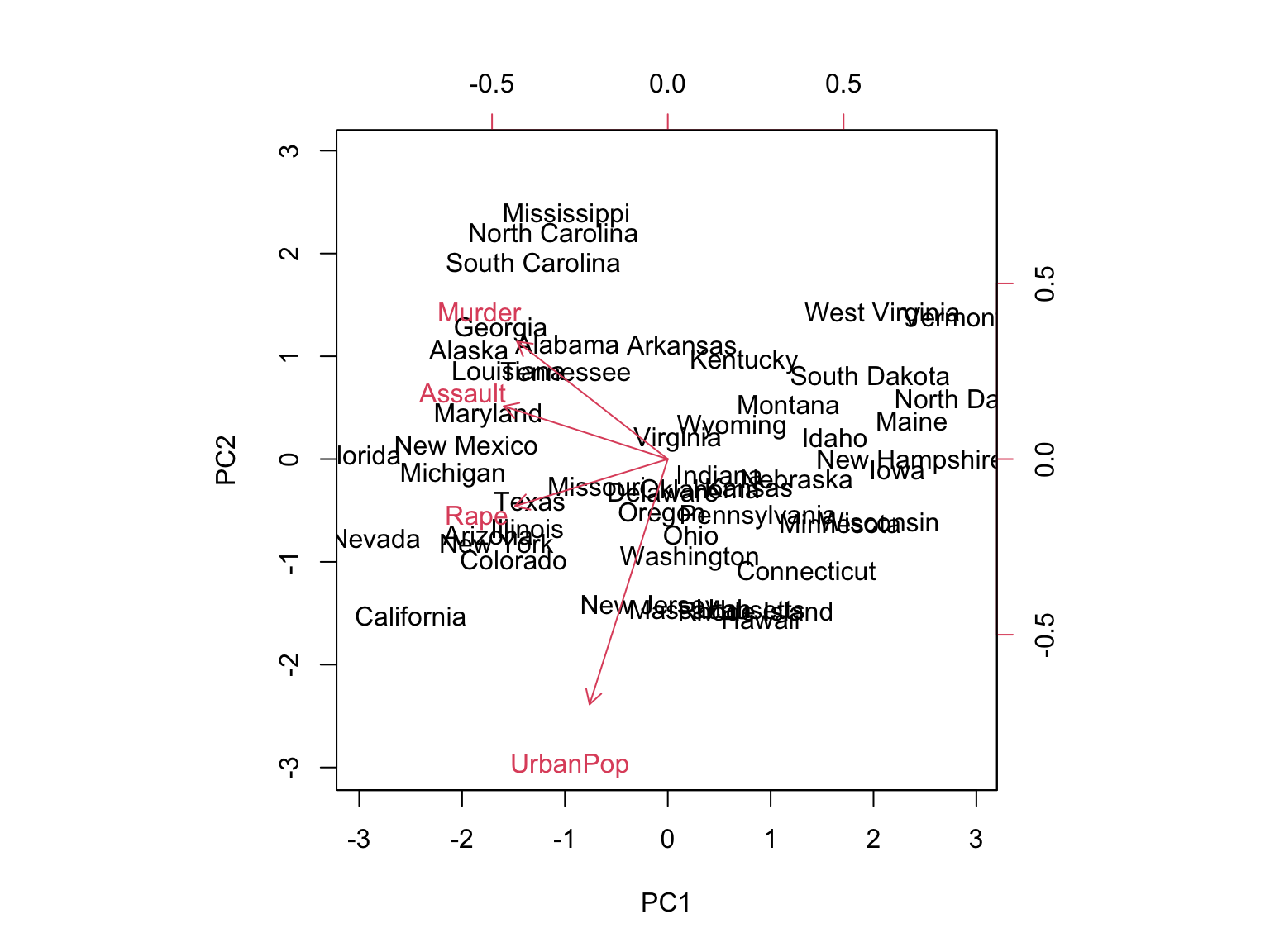

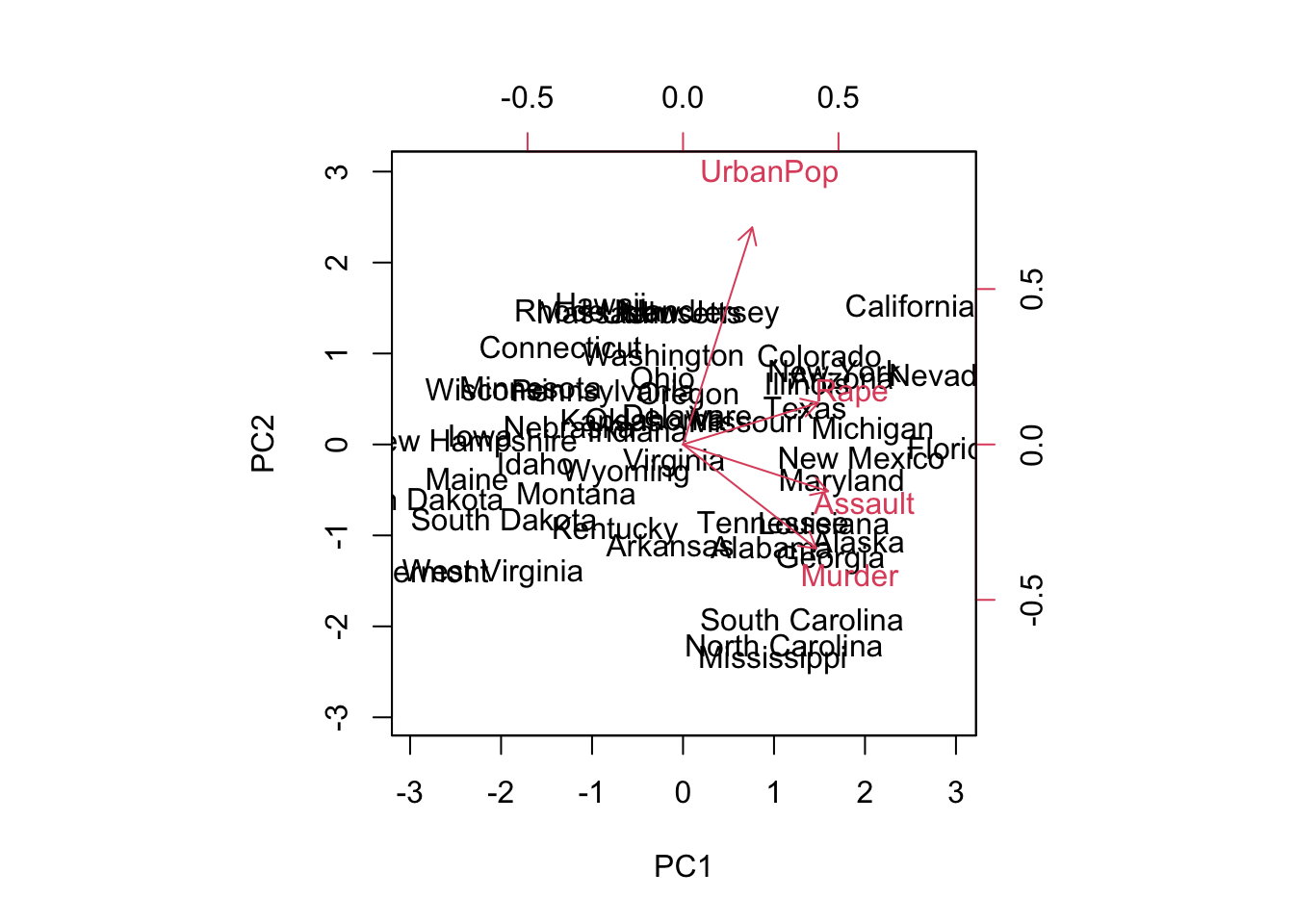

The prcomp() function is part of base R and provides an alternative way to perform PCA. Let’s use the USArrests dataset, which contains crime statistics for the 50 US states.

10.4.1 17.2.1 Data Exploration

# Load and examine the data

head(USArrests)

#> Murder Assault UrbanPop Rape

#> Alabama 13.2 236 58 21.2

#> Alaska 10.0 263 48 44.5

#> Arizona 8.1 294 80 31.0

#> Arkansas 8.8 190 50 19.5

#> California 9.0 276 91 40.6

#> Colorado 7.9 204 78 38.7

rownames(USArrests)

#> [1] "Alabama" "Alaska" "Arizona"

#> [4] "Arkansas" "California" "Colorado"

#> [7] "Connecticut" "Delaware" "Florida"

#> [10] "Georgia" "Hawaii" "Idaho"

#> [13] "Illinois" "Indiana" "Iowa"

#> [16] "Kansas" "Kentucky" "Louisiana"

#> [19] "Maine" "Maryland" "Massachusetts"

#> [22] "Michigan" "Minnesota" "Mississippi"

#> [25] "Missouri" "Montana" "Nebraska"

#> [28] "Nevada" "New Hampshire" "New Jersey"

#> [31] "New Mexico" "New York" "North Carolina"

#> [34] "North Dakota" "Ohio" "Oklahoma"

#> [37] "Oregon" "Pennsylvania" "Rhode Island"

#> [40] "South Carolina" "South Dakota" "Tennessee"

#> [43] "Texas" "Utah" "Vermont"

#> [46] "Virginia" "Washington" "West Virginia"

#> [49] "Wisconsin" "Wyoming"The dataset contains four variables:

- Murder: Murder arrests (per 100,000)

- Assault: Assault arrests (per 100,000)

- UrbanPop: Percent urban population

- Rape: Rape arrests (per 100,000)

colnames(USArrests)

#> [1] "Murder" "Assault" "UrbanPop" "Rape"10.4.2 17.2.2 Data Preprocessing: Why Standardization Matters

Notice that the variables have vastly different means. The apply() function with option 2 calculates statistics for each column (option 1 does it by row):

apply(USArrests, 2, mean)

#> Murder Assault UrbanPop Rape

#> 7.788 170.760 65.540 21.232There are on average three times as many rapes as murders, and more than eight times as many assaults as rapes. Let’s examine the variances:

apply(USArrests, 2, var)

#> Murder Assault UrbanPop Rape

#> 18.97047 6945.16571 209.51878 87.72916Important: The variables have very different variances. The UrbanPop variable (percentage) is not comparable to the number of arrests per 100,000. If we don’t scale the variables before performing PCA, most principal components would be driven by the Assault variable, since it has the largest mean and variance. It is crucial to standardize variables to have mean zero and standard deviation one before performing PCA.

10.4.3 17.2.3 Performing PCA with prcomp()

The option scale = TRUE scales the variables to have standard deviation one.

pr.out <- prcomp(USArrests, scale = TRUE)

names(pr.out)

#> [1] "sdev" "rotation" "center" "scale" "x"The center and scale components correspond to the means and standard deviations used for scaling:

pr.out$center

#> Murder Assault UrbanPop Rape

#> 7.788 170.760 65.540 21.232

pr.out$scale

#> Murder Assault UrbanPop Rape

#> 4.355510 83.337661 14.474763 9.36638510.4.4 17.2.4 Principal Component Loadings

The rotation matrix provides the principal component loadings; each column contains the corresponding principal component loading vector.

pr.out$rotation

#> PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4

#> Murder -0.5358995 0.4181809 -0.3412327 0.64922780

#> Assault -0.5831836 0.1879856 -0.2681484 -0.74340748

#> UrbanPop -0.2781909 -0.8728062 -0.3780158 0.13387773

#> Rape -0.5434321 -0.1673186 0.8177779 0.08902432We see that there are four distinct principal components. This is expected because there are generally \(min(n-1, p)\) informative principal components in a dataset with \(n\) observations and \(p\) variables.

10.4.5 17.2.5 Principal Component Scores

Using pr.out$x, we have the \(50 \times 4\) matrix of principal component score vectors. The \(k\)th column is the \(k\)th principal component score vector.

dim(pr.out$x)

#> [1] 50 4

head(pr.out$x)

#> PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4

#> Alabama -0.9756604 1.1220012 -0.43980366 0.154696581

#> Alaska -1.9305379 1.0624269 2.01950027 -0.434175454

#> Arizona -1.7454429 -0.7384595 0.05423025 -0.826264240

#> Arkansas 0.1399989 1.1085423 0.11342217 -0.180973554

#> California -2.4986128 -1.5274267 0.59254100 -0.338559240

#> Colorado -1.4993407 -0.9776297 1.08400162 0.00145016410.4.6 17.2.6 Visualizing Results

We can plot the first two principal components as follows:

biplot(pr.out, scale = 0)

The scale = 0 argument ensures that the arrows are scaled to represent the loadings; other values give slightly different biplots with different interpretations.

Note: Principal components are only unique up to a sign change. We can reproduce the figure by changing signs:

pr.out$rotation <- -pr.out$rotation

pr.out$x <- -pr.out$x

biplot(pr.out, scale = 0)

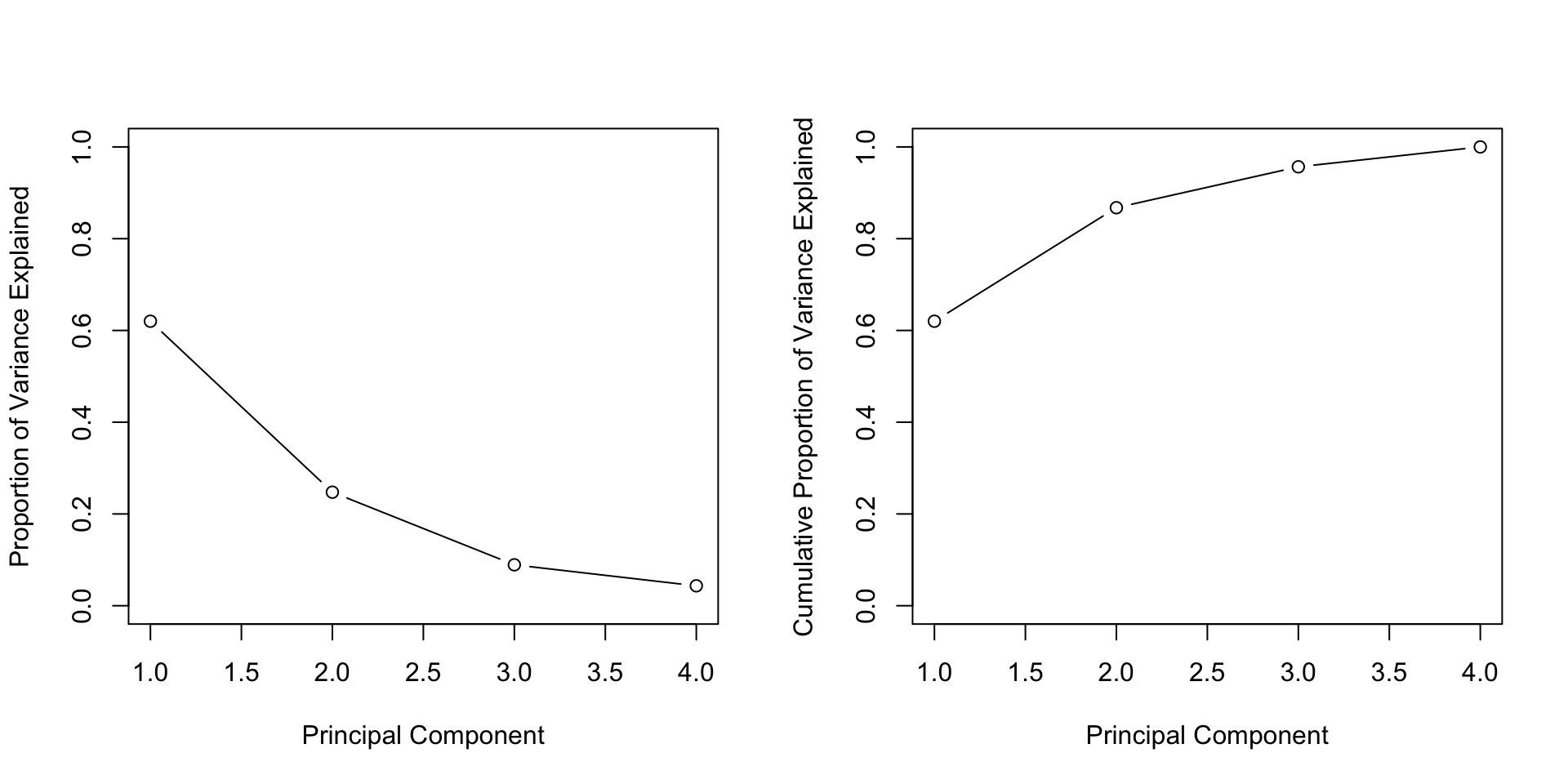

10.4.7 17.2.7 Variance Explained

The standard deviation (square root of the corresponding eigenvalue) of each principal component:

pr.out$sdev

#> [1] 1.5748783 0.9948694 0.5971291 0.4164494The variance explained by each principal component (corresponding eigenvalue) is obtained by squaring these:

pr.var <- pr.out$sdev^2

pr.var

#> [1] 2.4802416 0.9897652 0.3565632 0.1734301Compute the proportion of variance explained by each principal component:

pve <- pr.var / sum(pr.var)

pve

#> [1] 0.62006039 0.24744129 0.08914080 0.04335752We see that the first principal component explains 62.0% of the variance, and the next explains 24.7%. Let’s plot the PVE (Proportion of Variance Explained) and cumulative PVE:

par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

plot(pve, xlab = "Principal Component",

ylab = "Proportion of Variance Explained",

ylim = c(0, 1), type = "b")

plot(cumsum(pve), xlab = "Principal Component",

ylab = "Cumulative Proportion of Variance Explained",

ylim = c(0, 1), type = "b")

The function cumsum() computes the cumulative sum of the elements of a numeric vector.

10.5 17.3 Practical Exercises

10.5.1 Exercise 1: US Cereals Dataset

Consider the UScereal dataset from the MASS package (65 rows and 11 columns), which contains nutritional and marketing information from the 1993 ASA Statistical Graphics Exposition. The data have been normalized to a portion of one American cup.

Tasks:

- Load the dataset and examine its structure

- Identify which variables are quantitative and suitable for PCA

- Perform PCA on the quantitative variables

- Interpret the results: how many components should be retained?

- Create visualizations to understand the relationships between variables

10.5.2 Exercise 2: NCI Cancer Cell Line Data

Consider the NCI cancer cell line microarray data from ISLR2, which consists of 6,830 gene expression measurements on 64 cancer cell lines.

Tasks:

- Load the dataset

- Perform PCA on the gene expression data

- Visualize the first few principal components

- Check if the cancer types (given in

nci.labs) cluster together in the PCA space

10.5.3 Exercise 3: Wine Quality Analysis

Consider the wine dataset from the gclus package, which contains chemical analyses of wines grown in the same region in Italy but derived from three different cultivars. The dataset has 13 variables and over 170 observations.

Tasks:

- Perform PCA on the wine dataset. Remember to standardize the variables as they are on different scales.

library(gclus)

data(wine)

library(FactoMineR)

# Perform PCA

res.pca.wine <- PCA(wine, scale.unit = TRUE, graph = FALSE)- Interpret the PCA results. Focus on:

- Which chemical properties contribute most to the variance?

- Do the wines cluster by cultivar?

- How many principal components should be retained?

10.5.4 Exercise 4: Boston Housing Data

Consider the Boston dataset from the MASS package, which contains information collected by the U.S. Census Service concerning housing in the area of Boston, Massachusetts. It has 506 rows and 14 columns.

Tasks:

- Conduct PCA on the Boston housing dataset. Before performing PCA:

- Assess which variables are most suitable for the analysis

- Handle any missing values

- Preprocess the data accordingly

library(MASS)

data(Boston)

library(FactoMineR)

# Select appropriate variables and perform PCA

res.pca.boston <- PCA(Boston, scale.unit = TRUE, graph = FALSE)- Interpret the results. Look for patterns indicating relationships between:

- Crime rates

- Property tax

- Median value of owner-occupied homes

- Other housing characteristics

10.5.5 General Guidelines for Solving Exercises

-

Data Preprocessing: Before performing PCA, it’s crucial to:

- Handle missing values appropriately

- Standardize the data (especially when variables are on different scales)

- Select relevant quantitative variables

-

PCA Interpretation: When interpreting results, focus on:

- Eigenvalues and proportion of variance explained

- Loadings of variables on principal components

- Quality of representation (cos²)

- Contributions of variables and individuals

-

Visualization: Use plots to aid interpretation:

- Scree plots (eigenvalues)

- Biplots (variables and individuals together)

- Variable plots (with contributions or quality)

- Individual plots

- Contextual Understanding: Understanding the domain context can significantly help in interpreting results meaningfully. Always relate statistical findings back to the real-world problem you’re solving.

10.6 Online Resources and References

10.6.2 R Markdown Resources (as mentioned in slides)

- R Markdown Cheat Sheet: RStudio Cheatsheets - Download the R Markdown cheat sheet

- R Markdown Guide: R Markdown: The Definitive Guide

- RStudio: Download RStudio

- R Markdown Tutorial: R Markdown Tutorial

10.6.3 Tutorials and Guides

- PCA Tutorial: STHDA - Principal Component Analysis in R

- CA Tutorial: STHDA - Correspondence Analysis in R

- R-bloggers: Search for PCA and CA articles at R-bloggers.com

10.6.4 Interactive Tools

- PCA Visualization: PCA Explorer - Interactive PCA visualization tool

- R Documentation: rdocumentation.org - Search for PCA and CA functions

10.6.5 Books and Academic Resources

- An Introduction to Applied Multivariate Analysis with R by Everitt & Hothorn

- Principal Component Analysis by Jolliffe (classic textbook)

- Correspondence Analysis in Practice by Greenacre

10.6.6 Quick Reference

-

FactoMineR Help: Type

?PCAor?CAin R console after loading the package -

factoextra Help: Type

?fviz_pca_varor?fviz_ca_biplotin R console

⚠️ Important: If you encounter broken links in the PDF slides (module_2_PCA_&_CA.pdf), all the links above are verified and working. Use this section as your reference for online resources.